Broadway actor Kelvin Moon Loh had barely left the stage after a performance of “The King and I” in New York City this week when he felt he had to speak out about a situation involving a boy with autism in the audience.

During Wednesday’s matinee at Lincoln Center, Loh said a young boy with autism began making some loud noises during an intense “whipping scene” in the second act, drawing glares and some verbal admonishments from other patrons. Loh took to Facebook immediately after the performance and posted an passionate plea of empathy for the child and support for his mother.

“When did we as theater people, performers and audience members become so concerned with our own experience that we lose compassion for others?” Loh wrote in the post.

“I barely had my costume off and I was upset,” Loh told TODAY.com. “I felt like I had to say something. It’s just about having some kind of compassion, walking in their shoes and seeing how difficult it is to be in that position. It’s not like they walked in wanting to disrupt the performance.

“Parents of autistic children sit there with such fear and terror that this episode could occur. I was watching a mother’s nightmare happen, and I just wanted to have her know that what she’s doing is right in trying to expose her child to the theater, and there are advocates supporting her.”

Loh has not heard back from the mother of the boy since the Facebook post went viral, but has received hundreds of emails from other families that have children with autism.

Carrie Cariello, an author who runs the blog, ‘What Color is Monday?’, is a mother of five, including a son, Jack, 11, who has autism. She knows how that mother must have felt in that situation.

“The thoughts for me, and I have been in those moments, are, ‘What have I done? What was I thinking? Why can’t he control this?’ It’s just so much at once,” Cariello told TODAY.com. “I applaud [Loh] for reaching out to the public that way and I applaud the mother. I think in the end we’ll have to have these little painful stepping stones in order pave the road.”

Before Loh was a Broadway actor, he was a schoolteacher who worked in an after-school program with a child with autism. His fellow cast and crew members were also sympathetic to the boy and kept performing despite the noise and audience reaction.

“‘The King and I’ is a beautiful, family-friendly show,” Loh said. “Performances should be acceptable to any and every single person. The stares and the glares are not helping. Instead, reach out and ask how you can help as a person.”

“The greatest gift you can give to a family at that moment is to say, ‘What can I do for you?”’ Cariello said. “I think, believe or not, this is a win for the autism community. There are going to be small moments of discomfort on this journey.”

“I cannot help Jack make progress in the real world unless I bring him in the real world,” she said. “Every day, I fight for his place in your world, and every day I fight for your place in his world. If we sit home in our basements, which is easy and not stressful, that’s not growth for anybody.”

“My hope is people read the post and decide to act with kindness first before they cast a judgmental eye,” Loh said. “The theater is supposed to be for everyone.”

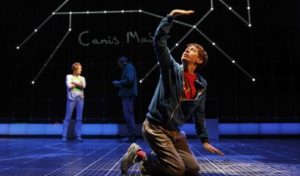

The King and I The varied manifestations of love: Ken Watanabe as the King and Kelli O’Hara as Anna in this revival of the musical at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center.CreditCreditSara Krulwich/The New York Times.

01/09/2015

A Broadway Hit, With an Autistic Math Whiz at Its Center

NPR Science Friday

The Kids Who Don’t Beat Autism

The other day a stranger called our house, out of the blue, to discuss my son Jonah’s health. He’d seen my memoir about our family and autism in the library and he wanted to know if I’d heard about a treatment that was getting remarkable results. Something to do with ocean water, he explained.

Incidentally, this sort of unsolicited heads-up isn’t as unusual as you would think. Not for me or any parent of a child on the autism spectrum. We’ve heard it all — from gluten-free diets to hyperbaric chambers. We’ve learned to tune it out, most of it anyway. But some trace of the miracle-cure talk echoes; it can’t be unheard. Ocean water, huh? As it happens, I told my mystery caller, we’re going to Maine next month.

I could have kicked myself.

But that’s the problem with this whole autism business; we want precisely what is not available to us — something definitive, like a cause, a cure. Enough, already, with the ambiguities, the gray zones.

Still, it was definitiveness that was worrying me when I began reading “The Kids Who Beat Autism,” Ruth Padawer’s cover story in the Aug. 3rd New York Times Magazine. Mainly, I didn’t want to discover all the things my wife, Cynthia, and I could have done and didn’t. That thought keeps me up enough nights as it is.

To her credit, Padawer leaves lots of room for ambiguity. She also raises important questions about one of the many persistent mysteries of autism: Why some kids do better than others. Why some kids recover.

According to the article, “two research groups have released rigorous, systematic studies, providing the best evidence yet that in fact a small but reliable subset of children really do overcome autism.” The conclusion reached by both studies is that the rate of recovery is about 10 percent.

But while the research may be new, the notion is not. Jonah, 15, received a diagnosis almost 12 years ago. We started his intensive applied behavioral analysis therapy immediately — 36 hours weekly — and once we did we heard a lot about kids who’d recovered. At the very least, we were told by our A.B.A. therapists, he could be “indistinguishable.” The word was held up to us like a beacon; for years, I repeated it like a mantra.

I also remember that shortly after Jonah’s diagnosis, when Cynthia and I felt as if our world was collapsing, another couple with a son on the spectrum invited us to dinner. We hardly knew them, but we knew of them. Their son, a few years older than Jonah, was attending a good school, doing well. “No one at school knows he has autism,” Cynthia said to me. “Can you believe it?” This couple and their son were an example of what the latest research studies call an “optimal outcome.”

I’m forever grateful to that couple for their kindness. They helped us through the first of many rough patches. Over the years, we lost touch; I’m not sure how their son is doing.

Jonah, meanwhile, is not indistinguishable. These days, though, there’s a lot more than his deficits in social interaction or conversation to distinguish him. There is, for example, the absolute delight he takes in jumping off the diving board or playing “Rocket Man” on his guitar. There’s also his openhearted, irrepressible personality. He’s a character. Last June, even his teachers, who had their share of trouble with him this past school year, grudgingly informed us, “The kid’s just so lovable.” As if we didn’t know.

It’s often said of spectrum disorders: “If you know one child with autism, you know one child.” The studies cited in the cover story make it clear the reasons some children recover and others don’t are not only inexplicable, they’re inexplicably random, an incalculable mix of early intervention, hard work and luck of the draw. It’s another gray zone — heartbreaking and reassuring at once — where those of us affected by autism live.